STUDY DAY #

##Modern Pre-Raphaelite Visionaries conference

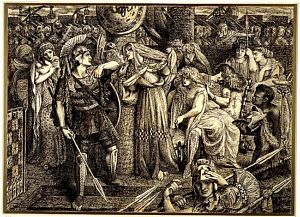

In a Wood so Green, Frederick Cayley Robinson

Date: 9 September 2022

Location: Art Gallery & Museum

Time: 9:00 - 15:30

The conference is open to all, but will be particularly suitable for academics, museum professionals, students, and those with a prior understanding of the field.

https://warwickdc.ticketsolve.com/ticketbooth/shows/1173631030/events?TSLVq=c5e02205-112b-4f6c-b93c-2fe3405377aa&TSLVp=19f95679-919f-47db-a965-c4919c99c292&TSLVts=1659101088&TSLVc=ticketsolve&TSLVe=warwickdc&TSLVrt=Safetynet&TSLVh=a6acc4285ce38cefa05a769e4465b5a2

https://warwickdc.ticketsolve.com/ticketbooth/shows/1173631030/events?TSLVq=c5e02205-112b-4f6c-b93c-2fe3405377aa&TSLVp=19f95679-919f-47db-a965-c4919c99c292&TSLVts=1659101088&TSLVc=ticketsolve&TSLVe=warwickdc&TSLVrt=Safetynet&TSLVh=a6acc4285ce38cefa05a769e4465b5a2

To celebrate our current exhibition, Modern Pre-Raphaelite Visionaries, British Art 1880-1930, Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum is organising a conference to explore the themes and ideas behind the exhibition and to examine the ongoing art historical legacy of this period in British Art.

This exhibition has offered the opportunity to re-examine a number of works by a host of ‘forgotten’ British Artists working at the turn of the twentieth century, whose work was inspired by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and European Symbolism, and who sought to understand their place in the changing modern world. It has allowed Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum’s important collection of work by Frederick Cayley Robinson, Simeon Solomon and William Shackleton to be contextualised by loans from across the country, raising the profile of these artists and their significance in the canon of British Art.

Please join us to discuss the life, work and significance of these artists on 9 September 2022 in person at the Royal Pump Rooms. The conference is open to all, but will be particularly suitable for academics, museum professionals, students, and those with a prior understanding of the field.

We are delighted to announce that Dr Elizabeth Prettejohn (University of York) and Dr Sarah Victoria Turner (Deputy Director at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art/ Yale University) will be giving the two keynote presentations at the conference. They will be joined by Dr Alice Eden (Research Curator, Modern Pre-Raphaelite Visionaries Exhibition) who will be discussing her work on the exhibition. The full programme of talks and speakers will be announced in due course.

Lunch, tea and coffee will be provided

Proposed Schedule (subject to amendment):

9:00-10:00 Registration, tea and coffee

The exhibition will be open for viewing to conference delegates before public opening hours

10:00- 10:15 Welcome

10:15-11:15 Dr Elizabeth Prettejohn - Revaluations: Stories of British Art 1880-1930

11:15-12:15 New Voices: Presentations by two Early Career Researchers

12:15–13:00 Lunch

13:00-13:30 Dr Alice Eden - Curator’s Introduction to Modern Pre-Raphaelite Visionaries

13:30-14:00 Break with chance to view exhibition

14:00-15:00 Dr Sarah Victoria Turner - “Cayley Robinson: a mystical modern”

15:00-15:30 Wrap Discussion

Cost: £15 standard / £5 concessions including students

This conference has been generously supported by the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. Modern Pre-Raphaelite Visionaries: British Art 1880-1930 has been supported by the Art Fund, the Garfield Weston Foundation, The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, the Albert Dawson Trust and Friends of Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum