Thursday 15 December 2022

Alice Boyd's Peacock

Saturday 26 November 2022

Tuesday 22 November 2022

Lord Monboddo's African manservant

On the famous tour of Highland Scotland taken by Dr Samuel

Johnson and James Boswell in 1773, the pair stopped off at the estate of jurist

Lord Monboddo [aka James Burnett], located in the Mearns [Kincardineshire]

south of Aberdeen. They left on 21 August,

according to Boswell’s journal:

Gory, my lord’s black servant,

was sent as our guide, to conduct us to the high road [to Aberdeen] The circumstance of each of them having a black

servant was another point of similarity between Johnson and Monboddo. I observed how curious it was to see an African

in the north of Scotland, with little or no difference of manners from those of

the natives. Dr Johnson laughed to see

Gory and Joseph riding together most cordially.

‘Those two fellows’ said he, ‘one from Africa, the other from Bohemia,

seem quite at home’.

Joseph was presumably manservant to either Boswell or

Johnson or maybe to both for this excursion.

‘Gory’ – named from Goree Island, Senegal, one of the slave-trading

sites in West Africa - was employed by

Monboddo, who was known for the ‘magnetism of his conversation’ and his ‘paradoxes’

or eccentric opinions, which included pre-Darwinian speculation over the relationship

between primates and humans. The

conversation at Monboddo House involved a sort of debate comparing or contrasting

the capacities of ‘the savage and the London shopkeeper’. To Monboddo citing ‘the savage’s courage’, Johnson

responded, ‘it was due to his limited power of thinking’.

With his notorious toast ‘to the next insurrection of the Negroes

in Jamaica’, Johnson was of course a notable opponent of enslavement on the

grounds of natural justice, though evidently unpersuaded of natural equality.

When Gory was about to part from

us, Dr Johnson called to him. ‘Mr Gory, give me leave to ask you a question! Are you baptized?’ Gory told him he was and confirmed by the

Bishop of Durham. [Johnson] then gave him a shilling.

Wednesday 16 November 2022

Alfresco Annunciation

Way back in 2020 I wrote on the correct title for Elizabeth Siddal's watercolour known as 'Haunted Wood',

when I drew attention to Rossetti's comparable rendering of the traditional Annunciation with Virgin Mary and Angel Gabriel also in an unusual outdoor setting.

Friday 28 October 2022

William Morris against Imperialism

on 12 November I give a talk for the William Morris Society on the subject of past and present views of British imperialism. Here are the proposed opening paragraphs

=====================

I will begin with or in Oxford, because it is so closely associated with WM and because there contested history of the unlamented British Empire is currently an active issue, as in respect of the sculpted figure saluting benefactor Cecil Rhodes on the external wall of Oriel College and the campaign Rhodes Must Fall.

As you see

it’s modest in size and protected from pigeons by a net that makes Rhodes look

as if he’s wearing a spiv’s checked suit. Demands for removal have prompted a

‘retain and explain’ response from Oriel.

Not far away, on a building where Rhodes lodged during his brief university career, is a complementary plaque praising Rhodes for the ‘great services’ he rendered to his country.

Meaning the

expansion/imposition of British political-economic interests in southern

Africa, extending from diamond exploitation to the nation Rhodesia created in

his name.

In summer

2022, the late unlamented Culture Secretary Nadine Dorries intervened in the

heritage listing process. Historic

England said this memorial did not merit legal protection; Dorries insisted it

was of ‘great historical significance’.

I don’t know the reasons she adduced.

But unwittingly she drew attention to both robber baron Rhodes and his

partner in diamond crime who installed the memorial plaque, Alfred Mosely. [No

relation to Oswald] Both made immense fortunes from the Kimberley

mines and in later life both spent part of this on ‘good works’.

[I suspect

Dorries confused Mosely’s plaque with Oriel’s statue, but as it happens the

former usefully cites Rhodes’s imperial impact rather than college benefaction] Just to recap: Rhodes’s commercial misdeeds

were underpinned by his racist ambition of world domination, to extend the

Empire, by bringing ‘ the whole

uncivilised world under British rule, recovering the US and making the Anglo

Saxon race but one empire.’

I will

return to the question of historic monuments.

But we can agree that WM did not celebrate Cecil Rhodes or his

colleagues in business or politics. To Morris, the British Empire was an ‘elaborate machinery of violence and fraud’. When for example the Colonial and Indian Exhibition opened in South

Kensington in 1886, he suggested alternative displays showing the death and

horror at the core of British policy.

WM’s anti-imperialism was an integral part of his Socialist convictions, but pre-dated those.

Thursday 22 September 2022

Sunday 4 September 2022

who is the boy? [10]

Sunday 28 August 2022

Who is the boy? [9]

|

| Laurens Alma Tadema, Head study, c1858, Walters AG Baltimore |

the model for this fairly roughly painted study was presumably a young man in Antwerp, there the artist studied and worked in the late 1850s. He wears a black shirt under a dark brown coat and a fur or rather wool-trimmed cap. An unlocated companion work depicting a profile head of the same sitter shows the cap was leather-crowned, with the deep astrakhan brim seen full face here and standing in for the boy's [presumed] dark curly hair. Presumed also a boy, because clean-shaven, although he might be quite a bit older. And presumed of African ancestry owing to his dark skin, and warm coat and cap against European winter. Therefore presumed to have been a seafarer, moonlighting it were in Antwerp between sailings.

But he could have been born anywhere from the Caribbean to Indonesia, and a permanent resident in Antwerp's busy entrepot. His abstracted expression suggests that the arftist was chiefly concerned with the work as a study in dark tones rather than portraiture, although the lad's static features are enlivened by the reflected lights on nose and lip.

Whatever, Alma Tadema was sufficiently pleased with both his studies of the unnamed model to take them with him when he moved to Britain, and keep them in his studio there.

Thursday 25 August 2022

who is the boy? [8]

|

| D G Rossetti, study of sleeping youth 1867 BMAG |

One African boy about which some fragmentary information is known is the sleeping child Rossetti added to his watercolour versions of the Return of Tibullus to Delia in the 1860s.

He was not, as has been supposed, the same lad who modelled for the Black child in Rossetti's Beloved of 1865. But a ship's boy recruited from the Sailors' Home or hostel in London's docklands. This was in same are as the the animal merchant Jamrach, from where Rossetti purchased his wombat and other creatures for his garden menagerie.

According to Harry Dunn, Rossetti's studio assistant, when DGR thought to introduce a house slave supposed to be guarding the threshold of Delia's Roman house, 'it was a puzzle where to find a regular little Nubian.' [Nubian being the preferred Victorian term for 'Black African' when the Nword wasn't used.]

Dunn, whose recollections are only partly reliable, then accompanied Rossetti to Whitechapel. 'Down many squalid streets we traversed and at last found ourselves in one broad thoroughfare abounding with ships drawn up close to shore, their bowsprits overlapping into the roadway. A motley crowd of sailors of all nations and garbs and tongue thronged the place; through this miscellaneous melee we passed until the Home was reached, and at last our search was rewarded by finding exactly the lad who was required; and with explanations to the object of our mission, it was arranged that the little fellow should make his appearance at Cheyne Walk the following day.

'The little Nubian came the next day, but as Rossetti remarked, he was so dusky that you could see his clothes moving about, but not the boy'.[H T Dunn Recollections 1984, 32-3]

The lad's near-invisibility perhaps owed more to the curtained gloom within the studio, and the poor eyesight that soon threatened the artist's livelihood, than to the tone of his skin, but does indicate his African origin.

It also contributed to his near-invisibility in the two coloured versions of the subject, one of which recently sold for £100k in London.

|

| DG Rossetti, The Return of Tibullus to Delia, watercolour, 1868, Sothebys July 2022 |

Look carefully and Tibullus is stepping over his sleeping form. [The brighter hues here in the 1867 version below are from the reproduction not the original]

|

| D G Rossetti, Return of Tibullus to Delia, watercolour 1867, unlocated |

Wednesday 24 August 2022

Who is the boy? [7]

|

| John Ritchie Winter, St James Park London, 1858 |

I've often wondered about this picture of Londoners on the frozen lake in St James' Park, and used it as an example of Victorian artists including a token Black figure in crowd scenes to convey urban diversity. The lad in the centre, skating so fast or inexpertly that he is about to crash behind the group of urchins, is well dressed in some kind of livery and top hat, so must be intended as a young footman who has escaped his household duties for the day. Were such servants still common in the 1850s, or is the artist alluding to an earlier social habit, when it was fashionable to have a [pair of] handsome Africans answering the front door and riding pillion on the family coach?

Ritchie (1828-1905) mostly concentrated on genre scenes as far as I can judge, but no more Black figures are visible in his known works - not even in the companion piece to Winter in St James' Park, Summer in Hyde Park, where all the picknicking and fishing characters are white.

Tuesday 23 August 2022

Who is the boy? [6]

|

| Peter Lely, Elizabeth Murray Countess Dysart c1651, Ham House |

It's clear from the composition of the portrait of Elizabeth Murray that the artist intended no relationship between her ladyship and the attendant; despite reaching for a rose on his proffered plate, she does not acknowledge his presence any more than she would a table.

His eyes, on the other hand, are anxiously fixed on her face, as if to see his service is approved. Pictorially it works, to affirm for the viewer her superior status and beauty - white skin, blonde ringlets, sumptuous silk and satin garments.

the suspicion that this is a stock figure for pictorial not biographical purposes is supported by a young fellow in another formal portrait by Lely [or his studio], where the lad reaches for orange blossoms and Lady Elizabeth remains impassive. Obviously, her portrait is the purpose of the image and she'd probably be depicted in much the same manner if her companion were her husband or child. These are not depictions of daily life and the details are all conventional.

|

| Peter Lely, Elizabeth Wriothesley Lady Noel c 1660s, Petworth |

Monday 22 August 2022

Who is the boy? [5]

|

| Wenceslaus Hollar, profile head of boy, 1635, FAM SF |

Sunday 21 August 2022

Who is the boy? [4]

|

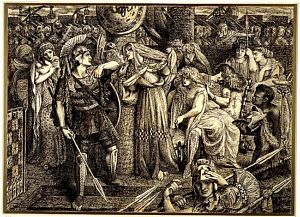

| D G Rossetti, design for Cassandra, 1861-7, BM |

The artist described in detail his overcrowded design for the Trojan scene of Hector refusing to heed Cassandra's prophecy before departing for his fatal encounter with Achilles. He listed all the figures apart from the kneeling Black youth who holds Paris's helmet in readiness for battle. Paris is still dallying with Helen, who's tying on his greaves in a very sexy manner.

In the list, even the Black nanny attending Andromache and baby Astyanax on the far left is mentioned. No models for any of the figures are named, however, and it's not possible to guess the identity of the Black youth. He is plainly not the same boy who sat for the child in Rossetti's Beloved. But his features are sufficiently distinctive to compare with similar figures in works by other contemporaries, and hence possibly guess as his origins, if not name.

DGR described the picture in the following terms: “The incident is just before Hector's last battle. Cassandra has warned him in vain by her prophecies, and is now throwing herself against a pillar, and rending her clothes in despair, because he will not be detained longer. He is rushing down the steps and trying to make himself heard across the noise, as he shouts an order to an officer in charge of the soldiers who are going round the ramparts on their way to battle. One of his captains is beckoning to him to make haste. Behind him is Andromache with her child, and a nurse who is holding the cradle. Helen is arming Paris in a leisurely way on a sofa; we may presume from her expression that Cassandra has not spared her in her denunciations. Paris is patting her on the back to soothe her, much amused. Priam and Hecuba are behind, the latter stopping her ears in horror. One brother is imploring Cassandra to desist from her fear-inspiring cries. The ramparts are lined with engines for casting stones on the besiegers.”

Saturday 20 August 2022

who is the boy ? [3]

A vibrant miniature of Peter the Great, Czar of Russia, painted by Gustav von Mardefeld, Prussian envoy to Petersburg. Peter is shown standing on the battlefield patting the head of the African attendant who holds Peter's helmet.

To increase Peter's stature literally and figuratively, the boy is depicted as very young. He has been identified as Abraham of Ibrahim Hannibal ( c1696-1781) who was kidnapped in Africa and adopted by [or presented to] Peter. He later became chief military engineer in the Russian Army. Alexander Pushkin was Hannibal's great-grandson, so there is an unusual amount of information.

But like so many, this ID may well be wishful. The portrait dates from around 1720 when Hannibal was in his 20s. Even if the image could have included a representation of Hannibal as he might have been on arrival in Russia, this cannot be a portrait of him as a boy. If painted from life, the sitter was yet another unnamed young African, shown in finery to enhance his companion's superiority.

Friday 19 August 2022

who is the boy? [2]

|

| William Dobson, John Byron, 1640s, Manchester U |

It would be great to find that the Byrons of Newstead had an African-born groom at this date. But as both opportunities and resources for portraiture were limited during during the War, it may also be that the African lad is a fictive figure, as it were, included to emphasise the status of this staunch supporter of Charles I. He must however have been drawn and painted from a living model. Or was the figure copied from a pictorial source?

As is doubtless the case. The horse was taken, albeit perfunctorily, from Vandyck's great equestrian portrait of Charles I, to enhance the swaggering demeanour of Byron, who was famously proud of the scar on his cheek. The attendant can probably be found in another aggrandising portrait of the era.

Kehinde Wiley used this painting as the basis for his own image of 1st Lord Byron, where a muscly Black model replaces the baron, and the attendant has been ignored.

|

| Kehinde Wiley, 1st Lord Byron, 2013, MFA Boston |

Thursday 18 August 2022

who is the boy ? [1]

There are so many black attendants in 17th and 18th European portraiture that it's hard to estimate their number. Virtually none are named, and one suspects that many were ciphers and signifiers rather than actual servants. Perhaps the art worlds had a stable of young Africans for use as required. There were enough such working in wealthy households to supply the demand.

Despite the ubiquity, it is worth noting their presence. As in the unattributed portrait of Sir John Chardin in the NPG [above] and Ashmolean [below]. The picture is so disregarded - because so commonplace - that when reproduced the Black boy holding up the maps is hard to discern. He is more visible in the monochrome image, which also shows the stupendously ornate frame to this painting.

The three-quarter 50-inch square portrait dates to about 1710 when French-born Chardin was in his 60s. Born in Paris, he was a jeweller and diamond merchant who settled in England, becoming famous for his travels to Persia and India, to seek gems and expand trade with the East. The maps in the portrait refer to these territories, so the servant is not signalling Caribbean properties, though quite possibly Chardin invested there.

In any event, he and the [as yet anonymous] artist chose to represent him with the fashionable accessory of the age, an enslaved attendant.

Wednesday 17 August 2022

Great Exhibition 1851

The famous Great Exhibition in London's Hyde Park in summer 1851 included contributions from around the globe in various sections showcasing industrial and agricultural produce, including those that would later develop into 'national pavilions'.

Many souvenir publications and images were created to register the Exhibition, including a series of coloured lithographs published Dickinson Bros, illustrating each section with its exhibits.

Artist Joseph Nash (1809-1878) was commissioned to produce pictorial records of the exhibition, and he enlivened the static displays by populating them with appropriately dressed figures, giving the impression of a global audience, albeit sparsely scattered instead of the crowded throng that flocked to the Crystal Palace.Thus the textiles, equestrian trappings, and leather goods from 'Tunis' have human accessories wearing fezes.

Sugar cane and sacks of unidentified raw material from Trinidad and Bahamas are accompanied by a nursemaid in typical Caribbean attire, in charge of white British children.

while India, grandest of all colonial possessions, with stuffed and caparisoned elephant, is shown with a visiting Moghul group of two men and a boy, escorted by a white gent in top hat.

all and more reproduced in Dickinsons' comprehensive pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851: from the originals painted for H.R.H. Prince Albert (Dickinson, Brothers, 1854).

Tuesday 16 August 2022

Fanny Eaton Memorial

|

| Mary & Brian Eaton in Margravine Cemetery. The white cross marks Fanny's burial spot. |

When Fanny Eaton died, she was buried in Margravine cemetery which stretches alongside the rail line between Barons Court underground station and the new Charing Cross hospital. Her family could not afford a gravestone, but now her descendant Brian has arranged for a memorial, which will be installed on 23 September. Photo to follow.

South Sea Bubble illustrated

Alas, not by a contemporary. A visual re-enactment rather like a dramatised documentary episode. By Victorian stalwart Edward Matthew Ward. One half of a prominent artistic partnership.

EM specialized in multi-figure costume dramas set in the Georgian era. Such as the Scene in Change Alley at the moment the South Sea Bubble burst. Set in 1820, painted and exhibited in 1847. Now in Tate Collection.

Also in Tate Collection is Ward's imagined image of Dr Johnson waiting vainly for admission to Lord Chesterfield's presence.

The two pictures include Africans attendant on fashionable ladies. They advertise Ward's historical knowledge. And perhaps in the South Sea Bubble painting, a reference to the South Sea Company's trading business in enslaved Africans.

Thursday 4 August 2022

The Young Catechist

I had not previously been aware that the painting The Young Catechist by Henry Hoppner Mayer, now owned by Bristol Art Gallery

https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/view_as/grid/search/works:the-young-catechist

was actually an illustration to verses by Charles Lamb. Holding her Book of Common Prayer the white girl is instructing the African in the responses to the Anglican catechism, which will lead to his baptism.

In fact, now I look more closely, Lamb's lines were in fact a literary illustration to the painting.

both are lamentable productions, even if their aims were laudable,

However, both are useful examples of the racist aspect to Abolitionist sentiments and campaigns in the 19th century.

Here's The Young Catechist poem

Tuesday 2 August 2022

Modern PR Visionaries UPDATE

STUDY DAY #

##Modern Pre-Raphaelite Visionaries conference

In a Wood so Green, Frederick Cayley Robinson

Date: 9 September 2022

Location: Art Gallery & Museum

Time: 9:00 - 15:30

The conference is open to all, but will be particularly suitable for academics, museum professionals, students, and those with a prior understanding of the field.

https://warwickdc.ticketsolve.com/ticketbooth/shows/1173631030/events?TSLVq=c5e02205-112b-4f6c-b93c-2fe3405377aa&TSLVp=19f95679-919f-47db-a965-c4919c99c292&TSLVts=1659101088&TSLVc=ticketsolve&TSLVe=warwickdc&TSLVrt=Safetynet&TSLVh=a6acc4285ce38cefa05a769e4465b5a2

To celebrate our current exhibition, Modern Pre-Raphaelite Visionaries, British Art 1880-1930, Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum is organising a conference to explore the themes and ideas behind the exhibition and to examine the ongoing art historical legacy of this period in British Art.

This exhibition has offered the opportunity to re-examine a number of works by a host of ‘forgotten’ British Artists working at the turn of the twentieth century, whose work was inspired by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and European Symbolism, and who sought to understand their place in the changing modern world. It has allowed Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum’s important collection of work by Frederick Cayley Robinson, Simeon Solomon and William Shackleton to be contextualised by loans from across the country, raising the profile of these artists and their significance in the canon of British Art.

Please join us to discuss the life, work and significance of these artists on 9 September 2022 in person at the Royal Pump Rooms. The conference is open to all, but will be particularly suitable for academics, museum professionals, students, and those with a prior understanding of the field.

We are delighted to announce that Dr Elizabeth Prettejohn (University of York) and Dr Sarah Victoria Turner (Deputy Director at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art/ Yale University) will be giving the two keynote presentations at the conference. They will be joined by Dr Alice Eden (Research Curator, Modern Pre-Raphaelite Visionaries Exhibition) who will be discussing her work on the exhibition. The full programme of talks and speakers will be announced in due course.

Lunch, tea and coffee will be provided

Proposed Schedule (subject to amendment):

9:00-10:00 Registration, tea and coffee

The exhibition will be open for viewing to conference delegates before public opening hours

10:00- 10:15 Welcome

10:15-11:15 Dr Elizabeth Prettejohn - Revaluations: Stories of British Art 1880-1930

11:15-12:15 New Voices: Presentations by two Early Career Researchers

12:15–13:00 Lunch

13:00-13:30 Dr Alice Eden - Curator’s Introduction to Modern Pre-Raphaelite Visionaries

13:30-14:00 Break with chance to view exhibition

14:00-15:00 Dr Sarah Victoria Turner - “Cayley Robinson: a mystical modern”

15:00-15:30 Wrap Discussion

Cost: £15 standard / £5 concessions including students

This conference has been generously supported by the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. Modern Pre-Raphaelite Visionaries: British Art 1880-1930 has been supported by the Art Fund, the Garfield Weston Foundation, The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, the Albert Dawson Trust and Friends of Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum

Wednesday 20 July 2022

Modern Pre-Raphaelite Visionaries

|

| Simeon Solomon, The Sleepers and one that Watcheth, 1871 |

RATHER a mouthful for the temporary exhibition at Leamington Spa art gallery [moving on to Watts Gallery in some form], chiefly because there’s no commonly used term for this brand of late Romantic painting in British Art 1880-1930 – the show’s more comprehensible sub-title.

The actual date range is even wider. Some exhibits are well-known: Rossetti’s

1864 Roman de la Rose; Simeon Solomon’s 1870 Sleepers and one that Waketh; Dicksee’s

1877 Harmony; Thomas Gotch’s 1896 Alleluia; Evelyn de Morgan’s

undated Queen Eleanor and Fair Rosamund.

Most however are unknown or new to public view and assessment. Frederick Cayley Robinson, who is the chief focus, is hardly known even to historians. Together the exhibition and its catalogue – both the work of Alice Eden – aim to position him in the interstitial space between 19th and 20th century fantasy. The focus is on mystery and enigma, which frequently arises from Robinson’s titles. The Foundling, for instance, is a fairly standard bedtime scene, where the child has fallen asleep by firelight and her mother lifts the coverlet prior to helping her into bed. But why ‘foundling’? the term sets the viewer hunting for cryptic clues to the girl’s origin. Is the bandage on her bare foot meaningful?

The Close of the Day is not dissimilar, especially in view of its candlelit

illumination, with three young women around a dim table with an open musical

box, a folio volume of something like an

illustrated periodical and a devotional painting hard up against a darkening

window. The commentary quotes a

contemporary account of Robinson’s atmospheres – ‘something is portending’ but we

don’t know what.

Puvis de Chavannes, Odilin Redon, Fernand Knopff and the Glasgow ‘Spook School’ all portend:

twilights, liminal spaces, dreamscapes, inaudible melodies feature in these

artworks, by artists trained in accurate drawing of observable objects and

figures.

A major inclusion are Robinson’s five crepuscular designs for Maeterlinck’s Blue Bird, which in its pre-1914 day eclipsed Peter Pan as a theatrical ‘must-see’. The Forest is especially resonant.

It links also to the Leamington cover-choice,

Robinson’s In a Wood So Green, where an aureoled St George rides through a

forest of slim birches oblivious of the sorrowing Princess whom he should surely

be saving. A good few stories can be inspired by this impenetrable piece.

.jpg)

.jpg)