Thursday, 31 December 2020

Hopeful New Year

Tuesday, 29 December 2020

Mantegna's Magi

All three Magi in this version wear pink surcoats. With Virgin and Babe being jostled by so many angelic Innocents [?] , the Kings take centre stage. All are relatively large, and would be very tall if their limbs were unfolded - especially the African King with his long legs and arms. His blue turban is on the ground. Only he has a retinue, with at least seven dark, turbaned attendants, and a couple of camels [are others obscured by the damaged patch?] It's a prodigious filmset landscape of papiermache rocks and a steep winding roadway leading directly to today's fantasy cinema.

Tuesday, 22 December 2020

Tough New Rules

Not, however, those locking us down more and more firmly, but changes to export licences for works of art and significance. Coming into force from January, announced by DCMS.

Now museums just [!] need funds to match auction and sale prices. But half a step is better than none...

Tough new rules crackdown on sellers to save important cultural items for the public

New rules will give museums and cultural institutions more protection when purchasing items for collections

- The increased protections will help prevent some of the nation’s greatest treasures from being lost to overseas buyers

- New rules will see an end to ‘gentleman’s agreement’ in first shake up of export deferral system in over 65 years

Culture Minister Caroline Dinenage has announced that new protections will be introduced for museums and galleries trying to save our most important treasures from overseas buyers.

Following a public consultation, the introduction of legally binding offers will see an end to the ‘gentleman’s agreement’ that has caused issues for UK museums and galleries when a seller pulls out at the last minute, causing fundraising efforts to be wasted and the work to be lost to public collections.

Under the current system, a pause in the export of national treasures overseas can be ordered by the Culture Minister to give UK museums and buyers the chance to raise funds and keep them in the country. If a UK institution puts in a matching offer on an item subject to an export deferral, and the owner has agreed to sell, it is down to the seller to honour that commitment.

Although a rare occurrence, in the last five years, eight items have been lost to UK collections when a seller refused to honor the ‘gentleman’s agreement’ resulting in months of vital fundraising work by national institutions going to waste. For example, in 2017 the National Gallery raised £30 million to acquire a work which was subsequently pulled from sale by the owner.

The new rules announced today will mean that this can no longer happen. The introduction of legally binding offers will mean that once a UK institution has stepped forward, and an owner has agreed to sell, then they must proceed with the sale.

Culture Minister, Caroline Dinenage, said:

Our museums and galleries are full of treasures that tell us about who we are and where we came from. The export bar system exists so that we can offer public institutions the opportunity to acquire new items of national importance.

It is right that this crackdown will make it easier for us to save items and avoid wasted fundraising efforts by our museums. It will mean that more works can be saved for the nation and go on display, educating and inspiring generations to come.

National Gallery Director, Dr Gabriele Finaldi, said:

I welcome the new rules that remove the ambiguities that have led to major works of art being lost to the nation. The clarity will be beneficial to museums and vendors alike.

Funds from the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport have also been made available for the development of a new digital system for export licences, which will be overseen by Arts Council England. This will allow sellers to apply for their export licence online, saving time, effort and expense for exporters. The new system is expected to be live by Autumn 2021.

The new rules, which will come into force on 1 January 2021, will be the first changes to the export bar system in over 65 years and reaffirm the Government’s commitment to the protection of our national treasures, owners’ rights, world-class museums, and the UK’s reputation as a successful international art market in light of the ongoing covid-19 pandemic.

Items that have been saved through the current system include the sledge and flag from Ernest Shackleton’s Nimrod Antarctic Expedition of 1907-09, which has been acquired by the National Maritime Museum and the Scott Polar Research Institute. Salvador Dali’s Lobster Telephone and Mae West Lips Sofa which were acquired by the National Galleries of Scotland and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Lawrence of Arabia’s steel and silver dagger which found a home at the National Army Museum, and the notebooks of Charles Lyell, Darwin’s mentor that were acquired by the University of Edinburgh.

In the ten year period to 2018-19, 39% of items at risk of leaving the UK - worth a total of £103.3 million - were saved for the nation by UK institutions.

ENDS

Notes to editors:

Until 1939, the UK had no legal controls on the export of works of art, books, manuscripts and other antiques. The outbreak of the Second World War made it necessary to impose controls on exports generally in order to conserve national resources.

Items that are being sold abroad are assessed at the point of application for an export licence by the Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest, which establishes whether an object is a national treasure because its departure from the UK would be a misfortune on the basis that it meets the ‘Waverley criteria’.

These are:

Is it closely connected with our history and national life? Is it of outstanding aesthetic importance? Is it of outstanding significance for the study of some particular branch of art, learning or history?

The export control process has always sought to strike a balance, as fairly as possible, between the various interests concerned in any application for an export licence.

The rules will apply to applications for export licences made on or after 1 January 2021. The form can be downloaded from the Arts Council’s website.

Friday, 18 December 2020

Sunday, 13 December 2020

Spartali vs De Morgan ?

No, i'm joking. I don't view these artists as rivals. Though the comparisons are interesting in respect of late-Victorian picture-making reputations.

Marie Spartali Stillman's now-famous and much-reproduced image of the lady Dianora in the Enchanted Garden of Messer Ansaldo, (1889) transformed from winter to spring by sorcery, finally came on to the art market last week and sold for £874,500 hammer price.

It's a lovely piece, in detail and in whole. A wonderfully Romantic scene, delicately and deliciously drawn and coloured. A bit fragile as regards condition - not surprising in a large 780 x 1000mm work on paper in Spartali's characteristically dry watercolour - and superbly reproducible in terms of merchandise.

The auction details and essay here

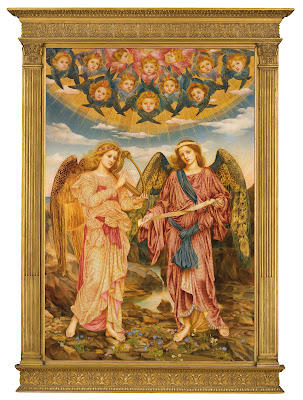

A few moments later, Gloria in Excelsis (1893) by Evelyn Pickering de Morgan depicting a pair of Christmas angels announcing the birth of Jesus to the Shepherds (not seen) with a host of seraphim in the sky, fetched £622,500.

see here Evelyn de Morgan

Evelyn De Morgan (1855-1919) | Gloria in Excelsis | 19th Century, Paintings | Christie's

It too is brilliantly drawn and coloured with elegant peacock wings and rippling drapery, but more robustly painted in oil and with an impressive pillared frame. The only drawback, in my view, are the juvenile Victorian faces of the seraphim, with windblown hair as if literally flying in heavenly air.

Both works came from the long-mysterious collection owned by Joe Setton. Both deserve to be publicly available for study.

A third female artist, much less well-known, in fact almost completely unknown, was represented by a small medievalising illustration of a girl trying a wedding ring for size.

By Alice Macallan Swan, this you might have bought for just £15,000, noting its Pre-Raphaelite debts to Rossetti's Ecce Ancilla and Millais's Bridesmaid.

The most intriguing and hitherto quite unknown work in the sale was lot 31, which depicts a medieval scholar in a midwinter library to whom an older necromancer reveals a vision of a rooftop garden overlooking ships at sea, with himself and an inamorata surrounded by courting couples and musicians.

The catalogue describes this as a version of Boccaccio's Messer Ansaldo tale. The authorship is ascribed to Rossetti's circle. Both seem good guesses, but not compelling ones. The main seated figure is reminiscent of Simeon Solomon's style, and the populated vision recalls the manuscript illuminations that were popular in the late 1850s. But what exactly is the story?

Untitled and unsigned, it sold for £40 000.

Tuesday, 1 December 2020

Black Magi sightings 2

As I discovered with Black Victorians, there turn out to be many more images than one imagines/knows of and certainly this elegant young Magus, who's carrying a jar of myrrh [and whom I'll call a Balthazar although there are disputes as to which King has which honorary name...] had previously escaped my knowledge.

He's from a late 15th century altarpiece in the Lichtenthal convent in south-west Germany, up a tributary of the Rhine, the gift of the abbess Margarethe of Baden. Now he's in NYC, in the Met's famous medieval section, together with his elder companions bearing gold and frankincense.Wednesday, 25 November 2020

St George the Moor?

The excellent new website Art and the Country House, edited by Martin Postle and published online by wonderful Paul Mellon Centre, aims to augment the Art Fund's presentation of paintings in public ownership in the UK with a selection from privately-owned collections. One of the latter is Mells Manor, Somerset, where the collection includes many works acquired by William Graham, the great Victorian collector of early Italian and Pre-Raphaelite art which were inherited by his Pre-Raphaelite-loving daughter, Frances Horner.

Among them is this little-known panel painting from the early 1400s depicting St George vanquishing the legendary dragon. The website's description by Paul Joannides

rehearses the evidence regarding possible artists, but factual information on provenance and other aspects is lacking and so despite its lively presentation and skilful rendering of armoured saint, rearing horse and writhing dragon in a constricted vertical space it is hard to guess if this was a free-standing panel or part of an ensemble.

Most striking to me is George' s dark complexion, on facial features that suggest African physiognomy. The most accessible medieval source for details of this Christian saint was Voragine's Golden Legend, which (when Englished by William Caxton in 1483 ) opens its hagiography thus:

S. George was a knight and born in Cappadocia. On a time he came in to the province of Libya, to a city which is said Silene. And by this city was a stagne or a pond like a sea, wherein was a dragon which envenomed all the country.

His deliverance of the king's daughter goes like this:

Thus as they spake together the dragon appeared and came running to them, and S. George was upon his horse, and drew out his sword and garnished him with the sign of the cross, and rode hardily against the dragon which came towards him, and smote him with his spear and hurt him sore and threw him to the ground. And after said to the maid: Deliver to me your girdle, and bind it about the neck of the dragon and be not afeard. When she had done so the dragon followed her as it had been a meek beast and debonair. Then she led him into the city, and the people fled by mountains and valleys, and said: Alas! alas! we shall be all dead. Then S. George said to them: Ne doubt ye no thing, without more, believe ye in God, Jesu Christ, and do ye to be baptized and I shall slay the dragon. Then the king was baptized and all his people, and S. George slew the dragon and smote off his head, and commanded that he should be thrown in the fields, and they took four carts with oxen that drew him out of the city.

Both Cappodocia and Libya in the middle ages were Muslim locations, as was the legendary site of George's body in a chapel between Jaffa and Jerusalem. So it could have been thought that he himself was of 'Moorish' origin. But Western artists were not in the habit of literal historicism. Normally, St George was a pale-skinned European, clad in the knightly armour of the artist's time.

So can one account for a depiction of George as brown-skinned?

I wonder if in this instance there was some kind of confusion or crossover with St Maurice, whom legend describes as a knight of the Roman Empire who was also ruler of Thebes which fancifully was said to be located in 'the parts of the East beyond Arabia', to be 'full of riches and plenteous of fruits' with inhabitants 'of great bodies and noble in arms, strong in battle, subtle in engine and right abundant in wisdom.'

Maurice was martyred along with scores of others who rendered unto Caesar but declined to worship the Caesar's deities and were slain en masse. Iconologically, late medieval images of Maurice depict him as an armoured knight of African appearance, as in the extraordinary painting by Cranach, now in the Met, New York.

Both Maurice and George have such splendid hats.

Friday, 20 November 2020

Lily Briscoe and Lisa Stillman

I have posted a speculative paper on the connections between the artist Lisa Stillman and the fictional character Lily Briscoe in Virginia Woolf's novel To the Lighthouse, based on the Stephen family holidays at St Ives, where Lisa executed a [now untraced] portrait of Virginia's mother Julia.

The images show Lisa as a girl in Florence and a young woman in New York

The text is here:

https://www.academia.edu/44511317/LISA_LILY_STILLMAN_BRISCOE_Nov_2020

Sunday, 8 November 2020

Willem Jerve Koetjie

|

| Add caption |

"You will be amused to hear that I have taken a little black (a Malay) into my service. He is a dear good boy." So wrote Alice, duchess of Hesse to her mother Queen Victoria in June 1863. "He has no religion, and can neither read nor write. I am going to have him taught and, later, christened. He is very intelligent, thirteen years old."

Sunday, 11 October 2020

Venetian Bust

Sunday, 27 September 2020

Fingers to the fire: Christina Rossetti’s mental health crisis

IT’s years since I published my biography of Christina Rossetti in which I speculated that her teenage ‘breakdown’ may have been linked to sexual trauma or abuse, and I have not kept up to date with much Rossetti scholarship, while nonetheless applauding the ongoing critical attention her verse now receives. But I ought to have been aware of the article by Simon Humphries in Notes & Queries, March 2017, where a summary account of Rossetti’s mental state by the physician who attended her in 1845 extends biographical understanding of these mid-teen years

Mackenzie Bell, Rossetti’s first

biographer, consulted Dr Charles Hare around 1895-6. After some delay, Hare, whom obits described

as a meticulous correspondent, explained he had sifted through over 8000

case notes to locate Rossetti’s, replying on 2 November 1896, when he was aged

78 (he died just two years later). As Humphries

shows, meticulously, the diagnosis of a nervous breakdown caused by ‘religious mania’

was not made by Hare but by other commentators. But Hare did describe Rossetti

when he was first consulted in November 1845 as ‘then 15’ (she was four or six weeks short of this birthday

) ‘and of a highly neurotic disposition and character.’ He was

the fourth medic to be called, which must reflect the family’s acute anxiety.

Although then denying that he

was disclosing the ‘medical memoranda’ or patient records which would ‘under no

circumstances whatever’ be made public, Hare continued to quote his case notes

as ‘matters of observation open to anyone at the time or mentioned in ordinary

conversation’. They actually read like a

record of what his patient told him.

‘Has been out of health for several months & a

marked change has taken place in her manner & in her way of speaking. When walking

out would suddenly leave her mother & turn back home, or run forward

without any cause & when asked why, said she did not know. Has said very

odd things—has also spoken of suicide; her spirits have been low & she does

no drawing or work of any kind.

‘She tells me that she

feels low & heavy & has a pain & heat almost constantly over a

small spot at the top (vertex) of the head;

this part is hot to the hand applied.—Is aware that she does not always express

herself correctly but she cannot help it; she does it from impulse.

‘She is usually very unwilling

to go out for a walk—feels too listless to do so: she does not like the effort

necessary to prepare for a walk though when out she does not object to the

walking. She tells me that she has a very strong impulse to burn her fingers as

by putting them on the hot bars of the fireplace: she knows that she will have

pain to suffer in consequence and she ‘does not like that better than anyone

else’; but yet she cannot help burning her fingers; she has done so 3 or 4

times the same morning.’

This reads as a vivid

description of behaviour in extreme psychic distress.

Hare continued to attend

Rossetti on a regular basis for the next five years (he recorded over 100

notes) and observe some improvement in her condition. However, in 1849 he was

again summoned, when she was ‘very weak’ and ‘confined to the sofa’, with pains

and ‘confusion in the head’.

‘I found that the headache had become more frontal:

her dreams were usually ‘frightful’ ones, & she had besides, ‘frequently

the sensation of vertigo or rather the sensation of things around

her—furniture, the walls, the floor—moving; the walls appear to be falling

gradually forward & the floor to have an undulating motion, & she sees

creeping things on the floor around her: mind sometimes wanders, she says very

odd things & is rather contrariant’ [sic]’

These alarming symptoms diminished ‘in a couple of

months’, although the pain in her head persisted. On 9 June she composed the poem, ‘Looking Forward’, writing out a copy for Hare

‘in her own neat handwriting’, whose title one could interpret as evidence that

she had resumed writing – although the content remained suicidal:

Sleep, let me sleep, for I am sick of care;

Sleep, let me sleep, for my pain wearies me…

Sweet thought that I may yet live and grow green,

That leaves may yet spring from the withered root,

And buds and flowers and berries half unseen;

Then if you haply muse

upon the past,

Say this: Poor child, she

hath her wish at last;

Barren through life, but in death bearing fruit.

All these symptoms,

but most especially the impulse to touch fire-hot bars, which allies with the ‘cutting’

incident recalled by her brother when she scored her arm with sharp scissors, surely

record the kind of self-harm often associated with severe teenage anguish - now

termed an ‘acute mental health crisis’ rather than a nervous breakdown. The migraine-like headaches, nightmares and hallucinations suggest a post-traumatic recurrence four years after the original

attack.

Of course I don’t

know what caused or precipitated Rossetti’s crisis in 1845 or its return in

1849. Those with professional knowledge of

teenage mental health whom I consulted in my turn spoke of self-harm,

dissociation and suicidal impulses being recognised traumatic symptoms of sexual abuse,

which in the context of Rossetti’s otherwise warmly affectionate family life seemed

a plausible suggestion. And I wish I

had known of Hare’s notes when I was researching

her life.

Tuesday, 22 September 2020

Hera by Marie Spartali Stillman

Marie Spartali Stillman’s painting Hera, which

although not ‘lost’ has remained fairly unknown, features in the forthcoming exhibition Artful

Stories, curated by Nancy Carlisle and Peter Trippi for the Eustis Estate

museum in Milton, Boston. It depicts

Hera/Juno, the patronal goddess of marriage and fertility, carrying a pomegranate

and a peacock feather, in the standard half-length format that MSS adapted from

renaissance and pre-Raphaelite examples for vaguely allegorical figures.

Probably painted in Rome, Hera is likely to have been a gift to Richard and Edith Norton, who were living in Italy. Richard was the son of Harvard’s Charles Eliot Norton, whom MSS knew through her husband, W.J. Stillman and British friends like Janey Morris. It is signed with MSS’s familiar monogram, and an indecipherable date that could be 1895 or 1905. The composition and especially horizon are very similar to other works by MSS, notably The Rose in Armida’s Garden (1894)

Some months ago, I was sent a jpeg of the 'new' Hera/Juno, which is that at the top of this post. One can see the rather nasty crack running through the support just left of the face. Happily, the Eustis exhibition has cleaned, conserved and mended the tear, so the painting looks very much better - as here below.

Tuesday, 15 September 2020

BMAG

This is a very welcome appointment. Birmingham's citizens are so energetic and engaged, trail-blazers for the heritage/arts sectors nationally.

Birmingham Museums Trust will have two new leaders in November when Sara Wajid and Zak Mensah step into their roles as joint CEOs of the organisation.

The announcement breaks new ground for both the trust and the sector; it is the first time the service will be led by a person of colour since it became a trust in 2012, and makes it one of just two organisations represented on the National Museum Directors’ Council to have BAME leadership. It is also one of the only instances of job-sharing taking place at the level of CEO in the museum sector.

The trust said the appointment is intended to cement its “commitment to representing the people of the city at all levels across the organisation”.

Wajid joins the trust from the Museum of London, where she is the head of engagement for the museum’s new capital project. She previously worked at Birmingham Museums Trust on a 15-month secondment, when she produced The Past is Now, the influential 2017 exhibition on the British Empire that pioneered decolonisation practice in the sector.

Mensah is currently the head of transformation at Bristol Museums, where he has played a significant role in growing the service’s income by 100% within three years, as well as leading programmes focusing on continuous improvement and technology.

The pair replace Ellen MacAdam, who stepped down in June after seven years in the role. They will be joining at a turbulent time for the trust, which currently undergoing redundancy consultations due the impact of the Covid pandemic.

Wajid said: “Being appointed as joint CEO to Birmingham Museums Trust is a very special honour for me and it’s in part thanks to the experience I gained on the arts council Change Makers programme at Birmingham Museums Trust in 2016. That's what I call effective anti-racist succession planning.

“Zak and I were inspired to apply for this role together through our involvement in Museum Detox (an anti-racist museum collective). We hope it could be a useful blueprint for others considering their future in the sector, and that we won't be in such a small cohort of people of colour leading museums for long.”